|

Examining Leadership: Retaining your talent |

||||||||

With all the emphasis on building and displaying leadership development, I've noticed that there seems to be a huge struggle with being able to retain the top talent. Having an existing leadership team in place that can identify the potential for others to grow is great, but they have to know what to do with those people once they get there. If there's an internal career superhighway for ambitious employees to pick up new skills and demonstrate themselves, there has to be an agreed, recognized end of the road, otherwise that career progression journey will take them straight out of the door into the market.

I've learnt that when you want to examining the talent growing process at any organization look at the culture, not the rhetoric – look at the results, not the commentary about potential. A disjoin in perception vs reality was accurately summarized from a recent industry survey, when employees were interviewed, here's what they said*:

- 1. More than 40% don't respect the person they report to.

- 2. More than 50% say they have different values than their employer.

- 3. More than 60% don't feel their career goals are aligned with the plans their employers have for them.

- 4. More than 70% don't feel appreciated or valued by their employer.

So, for all those leaders who have 'everything under control', you better start re-evaluating. The old saying that goes; "Employees don't quit working for companies, they quit working for their managers." Regardless of tenure, position, title, etc., employees who voluntarily leave, often do so out of some type of perceived disconnect with leadership.

In my experience I've found that employees who are challenged, engaged, valued, and rewarded (emotionally, intellectually & financially) rarely leave, and more importantly, they perform at very high levels. However if you miss one, or some of these critical areas, it's only a matter of time until they head for the open market.

Below are some key reasons that I've seen talent leave a company. As a leader, keep an eye out for these things and make sure you aren't doing them!

- 1. You Failed To Unleash Their Passions: Smart leaders align employee passions with corporate pursuits. Human nature makes it very difficult to walk away from areas of passion. If you fail understand this and you'll unknowingly be encouraging employees to seek their passions elsewhere.

- 2. You Failed To Challenge Their Intellect: Smart people don't like to live in a dimly lit world of boredom. If you don't challenge people's minds, they'll leave you for someone / somewhere that will.

- 3. You Failed To Engage Their Creativity: Great talent is wired to improve, enhance, and add value. They are built to change and innovate. They need to contribute by putting their fingerprints on design. Smart leaders don't place people in boxes – they free them from boxes. What's the use in having a racehorse if you don't let them run?

- 4. You Failed To Develop Their Skills: Leadership isn't a destination – it's a continuum. No matter how smart or talented a person is, there's always room for growth, development, and continued maturation. If you place restrictions on a person's ability to grow, they'll leave you for someone who won't.

- 5. You Failed To Give Them A Voice: Talented people have good thoughts, ideas, insights, and observations. If you don't listen to them, I can guarantee you someone else will.

- 6. You Failed To Care: Sure, people come to work for a paycheck, but that's not the only reason. In fact many studies show it's not even the most important reason. If you fail to care about people at a human level, at an emotional level, they'll eventually leave you regardless of how much you pay them.

- 7. You Failed to Lead: Businesses don't fail, products don't fail, projects don't fail, and teams don't fail – leaders fail. The best testament to the value of leadership is what happens in its absence – very little. If you fail to lead, your talent will seek leadership elsewhere.

- 8. You Failed To Recognize Their Contributions: The best leaders don't take credit – they give it. Failing to recognize the contributions of others is not only arrogant and disingenuous, but it's as also just as good as asking them to leave.

- 9. You Failed To Increase Their Responsibility: You cannot confine talent – try to do so and you'll either devolve into mediocrity, or force your talent seek more fertile ground. People will gladly accept a huge workload as long as an increase in responsibility comes along with the performance and execution of said workload.

- 10. You Failed To Keep Your Commitments: Promises made are worthless, but promises kept are invaluable. If you break trust with those you lead you will pay a very steep price. Leaders not accountable to their people will eventually be held accountable by their people.

To summarise, as a leader, you need to spend less time trying to retain people, and more time trying to understand them, care for them, invest in them, and lead them well, then retention will take care of itself.

*Statistics rounded out to show trending rather than specific figures.

|

Recruiters, treat your role advertisements as if they were first dates |

||||||||

My most recent interactions with recruiters, both from agencies and in-company, have left me slightly bemused by how they perceive the balance of the employee - recruiter relationship. I've had several experiences where this newly burgeoning relationship has felt very one sided from the very first contact and has been difficult to progress very far due to significant reluctance on the recruiters part to share any information at all.

Recognizing that their objective is to locate a candidate of sufficient quality to get into the face to face interview stage I can normally give them a little leeway in their single mindedness, but there seems to be a growing trend of only providing information pertinent to the employer, not the candidate.

So with the issue above in mind I've put this article together to explain the key elements that I think recruiters MUST include in their role advertisements to ensure that both candidates and recruiters have access to the information they need to make a reasoned, informed decision on the role. I've equated this to a dating analogy, as whilst thinking this through I found that I could draw some simple parallels between the two scenarios.

Think of the 'first date' scenario. Two different individuals meeting for the first time, each giving away small items of detail about themselves, revealing information that might make them appear more attractive to the other, but not quite revealing the entire picture. Each person is judging exactly what the best pieces of information are to reveal, what information they think will portray them in the best light, what will create additional interest, causing the other person to want to dig deeper, to create a more meaningful engagement. Each person has specific expectations from the other, there are typical subject that are normally covered and it all normally happens within certain civilized constraints, i.e. everyone wants certain snippets of common information, but is also aware of staying away from controversial topics. This is all jockeying for position to assess compatibility.

Now lets apply that thinking to the initial conversation between a recruiter and a candidate. Recruiters are trying to ensure compatibility between their role and the candidate, yet often they only come to the table armed with the specifics of the activities of the role and little else. Its fine for them to have demands of candidates, but in my view they also need to cover the following things to ensure that they are giving confidence and assurance to candidates that they actually care about compatibility with them.

- 1. Business model and moral compass: What the company actually does, how it makes its money, i.e. its business model and how it sees its self in society, i.e. its moral compass. How do you judge whether it is agreeable to your own, if this is omitted from the description?

- 2. Company sector and product set: What types of company are they? Financial? telecoms? Marketing? What do they sell or manufacture? It's not uncommon now to find advertisements that don't actually list what type of company they are, or whether the role is specific to a certain product set.

- 3. Salary and benefits: Always a controversial one this, but so many advertised roles do not feature a salary figure, or even a salary range to give an indication of where it sits within the market. This is a key factor for candidates, but also a key bargaining chip for recruiters so is often the last thing they give away. The other important factor with the salary figure is that it is an extremely good marker for the role's expectations. A high figure, or something that stands out from the market is likely to include other factors that in the role that warrant that figure. No salary is too good to be true, there will always be something in the role definition that has impacted that figure. An accurate figure also shows that the company advertising actually understands the role well themselves, and its position within the market. You have to balance this figure with the next point, the location.

- 4. The role location, and travelling demands: Pair this with the point above about salary and you have two key counterpoints to each other. Location obviously dictates where you base location is, but also consider travelling requirements as these can, and should have an impact on the salary. Regional locations, cities, secure sites and remote offices all play a factor in influencing both salary expectations and the level of comfort around commuting and the lifestyle impact taking the role may have on you.

To summarise, I think we need to redress the balance between recruiters and their market. If the four points above aren't covered in an advertised role then for me, it shows a lack of attention to candidates requirements, and a misunderstanding of how to create a quality engagement situation, that communicates what each party is actually looking for. If this was a first date, you wouldn't be getting a second.

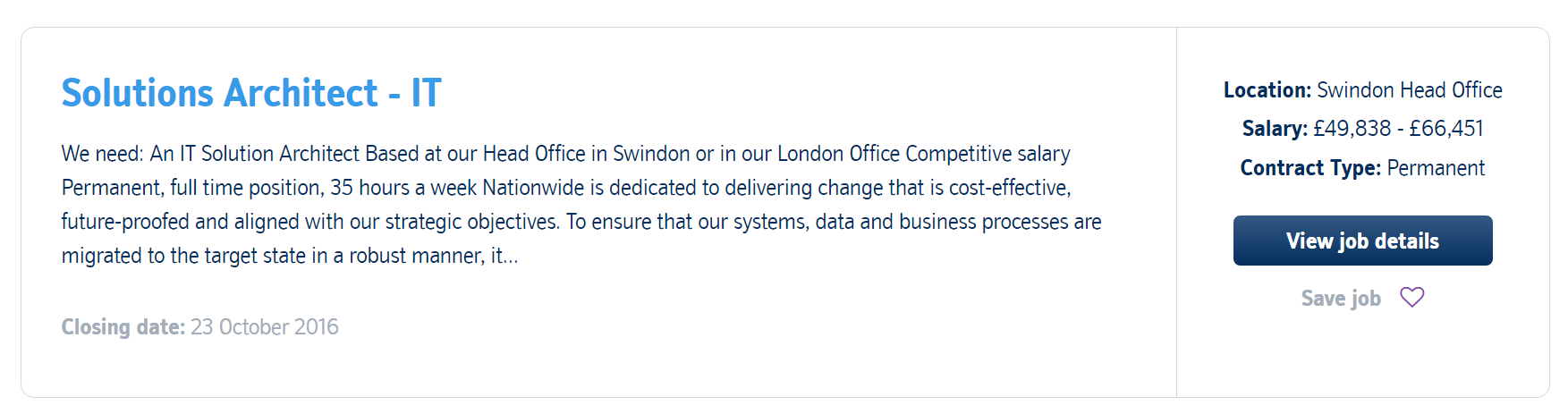

As an example of this, take a look at the following role advertisements:

|

Can an Innovation lab fit into the classic Corporate model? |

||||||||

At a recent company event one of the leaders in my division presented his thoughts on designing and implementing an Innovation lab. The presenter, Daryl Wilkinson, Head of Group Innovation at Nationwide (Link: @DarylAndHobbes) put forward the idea of creating a digital Agency style innovation lab. This would allow a select group of Thinkers, Strategist and Developers to rapidly wireframe up services and applications/widgets and quickly prototype them into working, running applications.

I think this is a very interesting opportunity, but I think the radically different approaches between operating an Innovation Lab and a large-scale UK Corporate company may pose some interesting issues.

Having worked in a few smaller companies, particularly digital and marketing agencies I can see the value in this. The benefits of this sort of approach are many, including increased flexibility, ability to change direction quickly and a more open way of communicating and moving ideas around. A key principle that allows this way of working to be productive for smaller companies is the removal of barriers. These barriers might be Company rigidity, Governance rules, formulaic team structures and employee ego. By removing all of these things, you can take away, or minimise their impact on the way people think about opportunities and problems. By removing traditional working barriers, you encourage people to open up to new ways of thinking that is not constrained by traditional learnt behaviour. (This is often referred to as disruptive thinking). The two fold acts of giving them literal authority to become unconstrained in approach, and the removal of these business rules allows for a different, more agile operational model.

This also results in the blurring of responsibilities and roles within the team. Team members are far more inclined to own their own space, and stretch out into other member's spaces, as the boundaries between them are blurred, in a far more collaborative working approach.

Let us contrast that with the traditional UK corporate model. Typically, they have a far more rigid structure, with defined lines between departments and responsibilities. Employees have a role to play and generally, because of the luxury of scale, people are kept in that role, and find it difficult to venture too far into other roles without encountering resistance.

Add into the corporate mix a defined, constrictive Governance model, security policies, hard-wired policies and processes and a corporate operating model, and the attitudes that brings with it. These elements are in direct conflict with the outline described above, that not only enables but also drives an Innovation lab. How this newfound Innovation lab will integrate into a corporate environment, working its way through the barriers described here, will either enable or contain its success. It will be a tricky journey implementing, then maturing a lab like this into a working state. It could become an interesting bubble of productivity, living inside the corporate structure, creating ripples that disrupt the usual state of thinking within traditional departments. What better way to introduce change into your organisation than by having a department like this forge new ways of thinking and approaches to solutions.

I'll certainly keep an eye on how it develops, and see if any of these conflicts arise.

|

The difference between Architecture and Design |

||||||||

In the last few weeks I've had many conversations with Architecture colleagues about the differences between Architecture and Design. These conversations don't typically start with this question, but more likely about the content of specific deliverables such as documents or strategy papers. Typically as an Architect you are required to deliver guidance on solutions as part of a project cycle, or as part of a larger overall programme. The point at which that guidance changes from 'Architecture' into 'Design' can be quite a contentious one.

For me, as an Architect, my responsibility is to guide the Strategy and direction of a project in terms of the technical aspects. I am effectively the technical manager, governing the direction that a project proceeds in. So how is that different from designing the solution yourself?

I like to think of Architecture as:

"Performing Governance and assurance around a solution to ensure that it aligns to Architectural principles, Strategic concerns and established patterns, in an elegant and cost effective way."

In plain English this is formulating which architectural principles are relevant and applicable, which patterns (in terms of both technical design patterns or business process patterns) are relevant and lastly whether there is an overarching strategy or strategies that drive the direction. It is effectively a set of rules, constraints and measures to guide the further direction of a solution (whether that is a project or a programme). It IS NOT the actual design of a solution but rather the instruction set that a design should use to build their design. When Architectural Governance kicks in and I review a designers design documentation, this is the rules set that I use to effectively 'mark their homework'.

Now, if we have defined the Architecture side of this argument, we should really do the same for the design side. This is a lot more real-world and far less abstract, normally because it is much easier to visualise than 'Architecture' is.

"Design is the process of collecting and placing business and technical building blocks to enable business capabilities."

Again, in real terms this means finding vendors, products and technical elements that fulfil as many of the identified requirements as possible, and arranging them in such a way as to enable an end to end business capability, usually by combining many simpler capabilities into a larger one.

Thinking of Architecture and design in this way makes it very easy to see where the boundary between these separate activities lays, which in turn means it becomes far simpler to see where any handover between resources should be, or where responsibility within a project lies. This sort of clarification also really helps to define the boundaries of an Architectural role, allowing them to focus on specific Architectural deliverables.